HANNA PAUL CAN RECALL THE EXACT MOMENT that inspired her research into Indigenous moon time teachings.

In 2017, while Paul was pursuing her undergraduate degree in anthropology and Indigenous studies, she volunteered at an Indigenous event that included a ceremonial element. At the time, she was on her moon time (menstruating) and was told she was unable to participate in the ceremony. Initially, Paul expected this to be because of taboo.

“Growing up all I knew was western taboos around menstruation,” says Paul, “But I was told that I was unable to participate because I was already going through a ceremony, a moon ceremony, and you can’t be in two ceremonies at one time.”

Many Indigenous cultures, including Métis, refer to menstruation as moon time, since it occurs on a 28-day cycle, similar to the moon’s cycle. This planted a seed for Paul that would grow into an Undergraduate Research Award and later her master’s thesis under the supervision of Dr. Fiona McDonald and Dr. Gabrielle Legault.

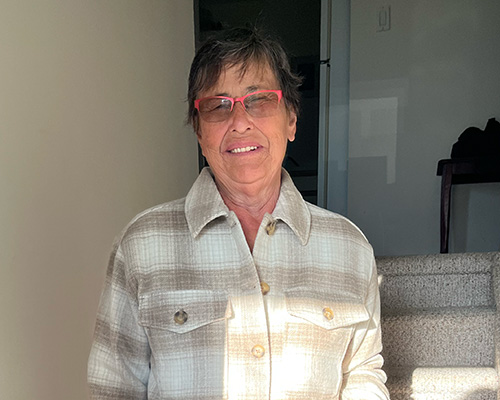

Hanna Paul’s kokum, pictured in her home.

Paul’s family history is diverse, with Métis and Beaver First Nation ancestry on her father’s side, and Ukrainian and French ancestry on her mother’s side. Her Métis family names are Paul, Lizotte, Lambert and LaFleur, and her community is located in the North Vermillion settlement, also known as Buttertown. Drawing on her heritage, Paul decided to return home to Buttertown for her master’s research to investigate whether Métis moon time teachings still existed there.

In summer 2022, Paul began her research project, living with her kokum (grandmother in Northern Michif and Cree), who helped her navigate her kinship relationships and connect with participants to discuss women’s teachings and Métis culture.

“My kokum was the best roommate and we quickly became friends in a way we weren’t able to be before,” says Paul. “She was at the intersection between being a researcher, being a community member and being kin because she was my local guide, my roommate and my kokum.”

Paul discovered that moon time teachings were not prevalent in Buttertown due to the colonial apparatuses of power that disrupted those teachings. Her research shifted to focus on how these teachings could be brought back and used to instill body image and self-esteem in youth and women.

“Shame and a lack of self-esteem were prevalent, derived from moments of cultural disruption,” says Paul. “We began to explore what it could look like to bring moon time teachings back to the community.”

Through a talking circle, Paul and her participants explored what Métis futurisms could look like in Buttertown and how moon time teachings could be mobilized to build confidence for future generations of youth and women.

Hanna Paul and her auntie picking Saskatoon berries in Buttertown.

Discussions during talking circles focused on the importance of place and community members having agency in telling their own stories. An interactive centre or place where these teachings could be shared within the community was a vision that came out of the calls to action in Paul’s research.

Upon returning to Kelowna and reflecting on her experiences, Paul recalls one of the most memorable parts of her summer: picking Saskatoon berries with her cousins and aunties. She knew she wanted this to be something central to her research. With the guidance of Dr. Shawn Wilson, the process of picking Saskatoon berries became an illustration of the methodology for Paul’s research.

“Journeying back home as a Métis community member and as a researcher created a really memorable summer for me. There were many parallels between my research and going to a berry patch,” says Paul. “Back home, you’d find a local guide to get you to a berry patch. My local guide was my kokum. Your guide may then help you find other berry pickers, just as my kokum helped me find participants.”

After completing her master’s degree, Paul plans to work with Indigenous youth and continue to situate herself within the Métis community. Ultimately, she hopes to pursue a doctorate based on the needs of her community.

The post Journeying back home appeared first on UBC Okanagan News.