THIS YEAR, MORE THAN 30,000 BRITISH COLUMBIANS WILL BE diagnosed with cancer, including 6,195 in the interior region. Sadly, those numbers will continue growing year on year; according to BC Cancer’s projections, the number of new cancer cases in the region is expected to increase by 27 per cent from 2019 to 2034.

Following specialist treatment, many of them will go on to live long lives in the care of their family physicians, nurse practitioners or other primary care providers, thanks in part to early detection, improvements in technology and more effective treatments.

Dr. Siavash Atrchian from BC Cancer-Kelowna.

For Kelowna-based BC Cancer radiation oncologist Dr. Siavash Atrchian, a clinical assistant professor in UBC’s Faculty of Medicine and a radiation oncologist at BC Cancer-Kelowna, ensuring the best outcomes for his patients means understanding how best to integrate family physicians into their care.

“Overall, in the patient cancer journey, I think family doctors play an extremely important role, from the start to the end,” says Dr. Atrchian. “As oncologists, we can’t follow our patients forever once their cancer treatment has been completed. I’m very interested in seeing whether we can improve this journey. How can I do a better job in my role? How can I communicate better with other care providers?”

These questions were on his mind when Dr. Atrchian was first introduced to Dr. Christine Voss, an investigator at UBCO’s Centre for Chronic Disease Prevention and Management, in 2019. Dr. Voss, who was just helping to launch the Centre’s Clinical Research and Quality Improvement (QI) Incubator Program, was intrigued at the opportunity to help tease out some answers.

“The premise of the incubator initiative is really to bring health scientists together with clinicians,” Dr. Voss explains. “In Dr. Atrchian, you have a clinician who really understands the needs around post-cancer treatment, while I’m a scientist who knows how to set up a mixed-methods study, collect and analyze the data,” Dr. Voss adds. “I recommended interviews and surveys of family physicians and oncologists in Interior Health, and was able to guide how to set those up.”

Dr. Voss and Dr. Atrchian soon became co-principal investigators of an interdisciplinary team of researchers, oncologists, family physicians and Southern Medical Program students, with the goal of examining how to best integrate family doctors into the post-cancer treatment care of the four most common cancers: breast, lung, colon and prostate.

To conduct the information-gathering for their research, Dr. Voss and Dr. Atrchian tapped then-first-year UBC Southern Medical Program student Brian Hayes, who took it on as his FLEX project. Having already completed a Master of Science in Kinesiology at UBC Vancouver, Hayes was eager to participate in research that would inform his journey toward becoming a doctor and directly benefit patients.

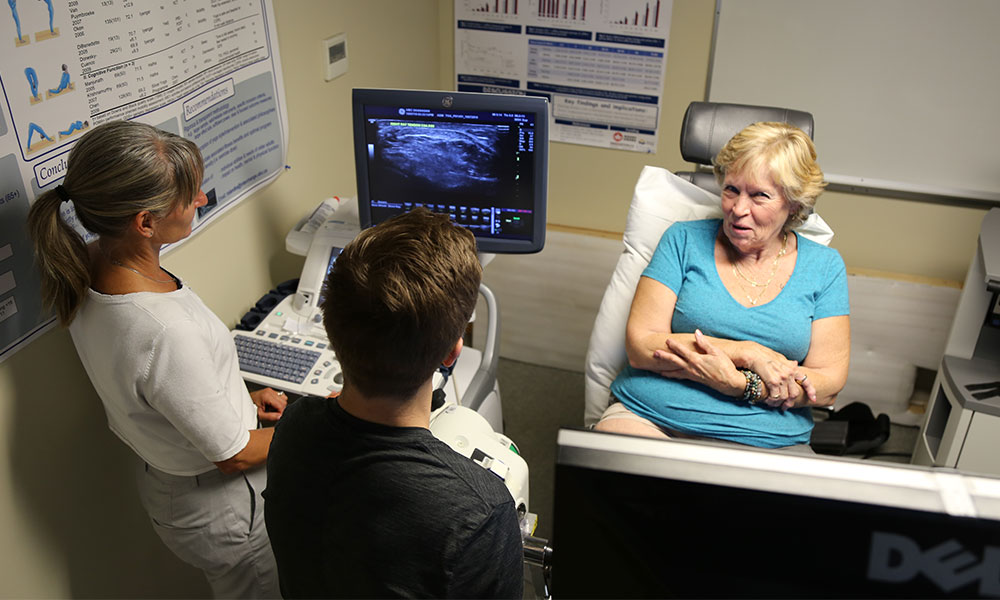

Dr. Christine Voss was intrigued by the opportunity to work with BC Cancer’s Dr. Siavash Atrchian to understand how to better integrate family physicians into patients’ post-cancer care.

“I wanted to research something more similar to where I saw myself practicing,” Hayes explains. “I was thinking about family medicine as a possible career path, and the project sounded really interesting, doing interviews and surveys and talking to doctors. This seemed like a big quality-improvement, big-picture kind of project that I found interesting.”

A year into the project, Hayes suggested bringing his classmate Hannah Young on board, who jumped at the chance to get involved. “Being from a rural community and wanting to practice rural family medicine, I thought this was right up my alley in terms of improving and optimizing the health care in those rural areas for cancer patients,” she says. For those living in rural areas, acute cancer care can involve additional travel for treatments like chemotherapy and radiation; when they complete their active treatment, they will be relying heavily on their family doctors for ongoing follow-up care.

Young was tasked with helping to design and distribute anonymous surveys to 943 family physicians and 39 oncologists throughout BC’s interior about their experiences working with one another to support cancer patients. When the surveys came back with a high response rate—25 per cent for the family physicians, and close to 100 per cent for the oncologists—the research team was thrilled.

“It was really neat, because when you start getting results you realize how tangible this research is, and that the work you’re doing is connecting with real people,” says Young. “By making the lives of the physicians better, by working toward different strategies to improve care, you’re also helping so many patients as well.”

Southern Medical Program students Brian Hayes and Hannah Young worked together on a research project to help improve health care for cancer patients living in rural areas.

Having seen first-hand what a diagnosis of cancer means for people living in rural areas, Young understood the importance of what Dr. Voss and Dr. Atrchian were doing. “I’ve definitely seen how difficult it can be to access treatment in a rural community when you’re having to travel far distances for specialist care. Especially if you’re in pain, and with all the stress, it can be really, really hard.”

The team is still working on analyzing the data they’ve collected and will be submitting their results for publication, with Young and Hayes as first authors—a highly valuable experience for both. While it’s too early to share details of their findings, Dr. Atrchian says the work is revealing how cancer patients’ post-treatment journey can be better supported by those caring for them. That includes bringing oncologists and family physicians together for more regular educational sessions; more robust guidelines for discharge notes from oncologists to family physicians; and creating more opportunities for them to communicate with one another.

Delivering actionable results that could result in improved patient care is something Dr. Atrchian feels particularly passionate about. “There are many components that I, as a clinician, can’t do anything about, like hiring more doctors or addressing wait times,” he observes. “But I can find out, ‘How can I help myself? How can I do a better job? How can I communicate better?’ to improve this patient journey. I hope that this research is going to trigger other people to think about it, and come up with other brilliant ideas about how we can improve.”

The post A team approach to understanding post-treatment cancer care appeared first on UBC Okanagan News.