What is your PhD focus? Why is this area of study important?

Public infrastructure is critical to citizens’ health, safety and economic prosperity. According to Canada’s 2016 national infrastructure report card, a large portion of wastewater infrastructure is in poor to very poor condition, requiring a replacement cost of more than $26 billion. A similar pattern can be seen in wastewater pipe condition grades in the United States. Risk-based infrastructure management is required to assess conditions and assist decision-makers in prioritizing inspection, renewal or repair. This is where my expertise comes into play: I develop decision-support tools for managing municipal infrastructure and reducing risk associated with oil and gas pipelines.

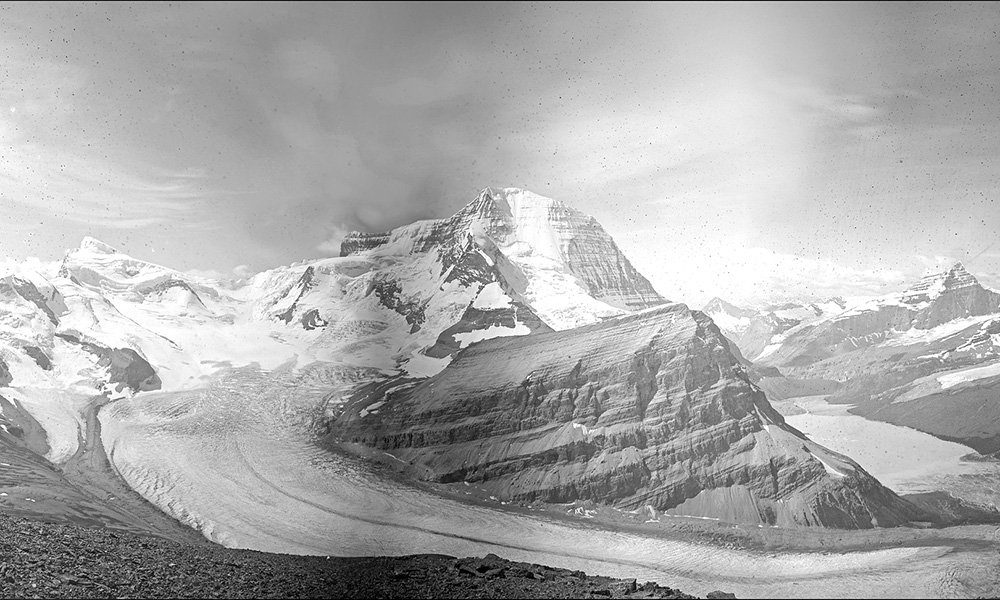

My father had a significant influence on my interest in civil engineering, particularly in the field of infrastructure asset management. At a young age, he used to take me almost every week to the eastern escarpment of my home country, Eritrea, to see the century-old railway system. The discussion we had was eye-opening and inspired me to focus on maintaining infrastructures so that it lasts.

What’s the best advice you have for other students, whether they are undergraduate, graduate or doctoral?

My advice to undergraduate students is to devote time to reading and understanding the program in which they’re enrolled. This is the best time to learn new skills and expand knowledge. It serves as the basis for future studies, so lay the foundation carefully from the start

Graduate students should begin working on projects that they are passionate about. When choosing a supervisor, conduct a thorough investigation. You will enjoy your graduate years and learn a lot more if you work with someone knowledgeable and passionate about the same topic as you.

My final piece of advice for undergraduates and graduates is to balance your personal and professional lives. Life is more than just school.

Do you have a mentor? If so, how have they influenced you?

Haile Woldesellasse in his home country of Eritrea.

My parents and siblings are my immediate mentors in my life. My mom, with her wisdom and constant support, encouraged me to stay focused on my objectives when the road seemed tough and impossible. My dad is a giant beacon who has given me guidance from his experiences and always recommends books that have benefitted me at different stages of my life. I also have close friends who advise me on many aspects of life.

My supervisor, Dr. Solomon Tesfamariam, has also been an excellent mentor throughout my doctoral studies. From the beginning, he has been a driving force in my research. His work ethic, critical thinking and attention to detail all had a significant influence on my technical and research skills. Above all, he gave me opportunities to grow as a researcher.

What are some challenges you’ve faced so far in your academic career?

Earning a doctorate is a commitment that requires a significant amount of time and energy. This becomes more difficult during the winter, when you don’t get enough sunlight and your activities are limited in many ways. It was also difficult not having my family with me.

How do you balance school and home life?

Even though the majority of my time is taken up by work on my research or publishing, I try to find some balance between school and home life. Tennis is one of my favourite sports and I have been playing since I was young. Last year I joined the UBCO Tennis Club and play on the weekends. I also go for hikes, read philosophical books and above all I enjoy spending quality time with my family and friends.

What do you see yourself doing 10 years from now?

I see myself with enough work experience to give back or transfer my knowledge to young researchers who are interested in pursuing their ideas. I also want to use my engineering background to help develop sustainable infrastructure that will benefit society.

What do you think makes UBCO great?

First, UBCO has a reputation as being one of the top-ranked best universities in Canada. The community is very connected, and Kelowna is becoming popular among families and young professionals. The university provides a high-quality education and access to cutting-edge research, not to mention the beautiful outdoor areas and scenery of the Okanagan.

The post Haile Woldesellasse wants to give back in many ways appeared first on UBC Okanagan News.