New research from UBC Okanagan suggests that understanding gut microbiomes of immigrants is important to understanding how westernization is driving immune responses like IBD.

Indian immigrants and Indo-Canadians who adopt westernized dietary practices experience a greater risk of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)—while supplements and probiotics often recommended may not provide the same benefits to certain demographics, new research from UBC Okanagan reveals.

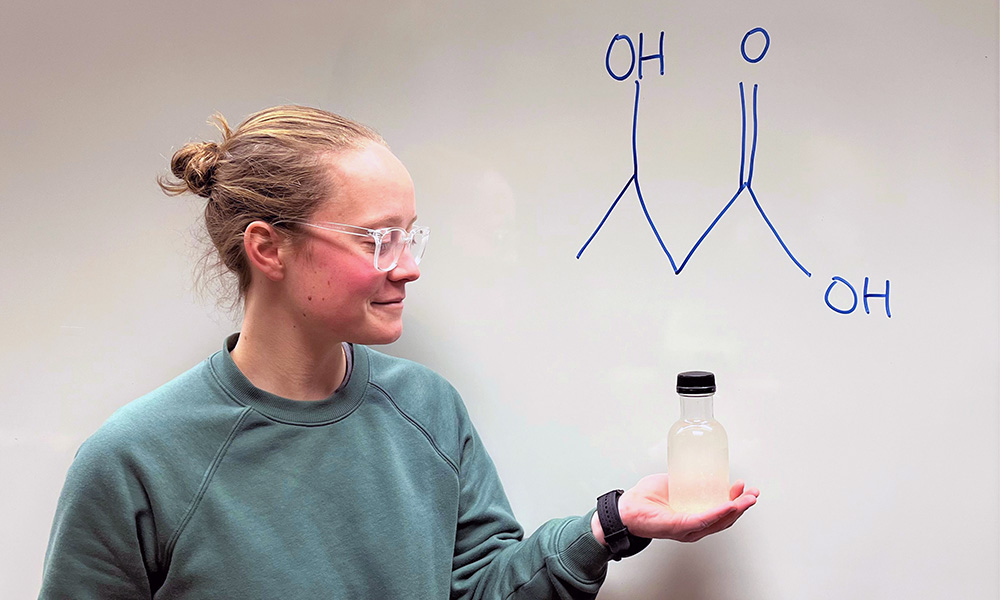

Leah D’Aloisio, a Master of Science student in UBCO’s Department of Biology, and her thesis adviser, Dr. Deanna L. Gibson, worked in collaboration with colleagues from the UK and India to better understand the daily challenges experienced by Indians adapting to new cultures.

They’re currently investigating how westernization affects the gut microbiome and makes them more susceptible to IBD.

D’Aloisio’s research involves collecting stool samples from Indians living in India, Indian immigrants and Indo-Canadians. She analyzes their gut microbiome composition using DNA sequencing. She also collected additional data including dietary habits, lifestyle changes, health status and socioeconomic information.

When comparing the microbiomes of those living in India compared to Euro-Canadians, she’s found that the gut microbiomes in Indians are extremely different from Euro-Canadians.

“I really want people to understand the differences that exist in the human gut microbiome,” D’Aloisio says. “It looks drastically different depending on where you’re born and your overall lifestyle, so if you’re an immigrant here in Canada, think about that… And know that the research that led to creating these ‘gut health’ products you see marketed to you today is likely not representing you. Take time to rethink this before you spend your money. You don’t want to introduce a species into an ecosystem that is not meant to be there.”

According to D’Aloisio, her research has important implications for public health and clinical practice. She hopes that her findings will raise awareness about the influence of westernization on the gut microbiome and health outcomes of immigrant populations.

She also suggests that interventions such as dietary counselling, tailored probiotic supplementation and stress management may help prevent or treat IBD among Indian immigrants.

Dr. Gibson started this project thanks to funding from a UBC Killam research award that supported a sabbatical where she was able to collaborate with several high-profile research institutes in Kolkata and Manipal, India. Understanding the gut microbiomes of various populations outside of westernized countries is important to understanding how westernization is driving dysregulated immune responses like those in IBD.

The post Canadian gut health products may not provide the same benefits to immigrants, UBCO researchers say appeared first on UBC Okanagan News.