A new UBCO study found that microdosing psilocybin demonstrated greater improvements in mood, mental health and psychomotor ability for participants.

The latest study to examine how tiny amounts of psychedelics can impact mental health provides further evidence of the therapeutic potential of microdosing.

Published in Nature-Scientific Reports this week, the study followed 953 people taking regular small amounts of psilocybin and a second group of 180 people that were not microdosing. This research, led by UBC Okanagan’s Dr. Zach Walsh and doctoral student Joseph Rootman is the latest study to come from the Microdose.me project.

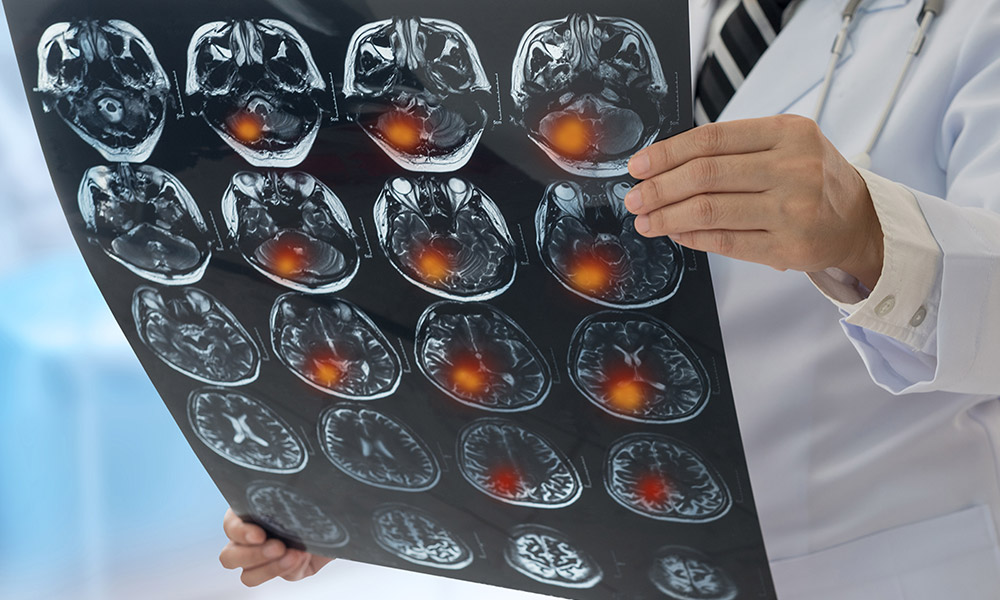

For the 30-day study, participants were asked to complete a number of assessments that tap into mental health symptomology, mood and measures of cognition. For example, a smartphone finger tap test was integrated into the study to measure psychomotor ability, which can be used as a marker for neurodegenerative disorders including Parkinson’s disease.

Those microdosing demonstrated greater improvements in mood, mental health and psychomotor ability over the one-month period compared to non-microdosing peers who completed the same assessments.

“This is the largest longitudinal study of this kind to date of microdosing psilocybin and one of the few studies to engage a control group,” says Dr. Walsh, who teaches in the Irving K. Barber Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences. “Our findings of improved mood and reduced symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress add to the growing conversation about the therapeutic potential of microdosing.”

Large doses of psychedelic psilocybin mushrooms have a long history of use among some Indigenous peoples and are prized in Western culture for their psychedelic effects, explains Dr. Walsh. They were also labelled an illicit substance during the American-led “war on drugs.” But recent interest has expanded from large dose psychedelic use—known for creating dramatic alterations in mood and consciousness—to the potential therapeutic application of smaller microdoses. Amounts so small they minimally interfere with daily functioning.

The Microdose.me project is conducted by an international team including Dr. Pam Kryskow from UBC Vancouver, Maggie Kiraga and Dr. Kim Kuypers from Maastricht University in the Netherlands, American mycologist Paul Stamets, and Kalin Harvey and Eesmyal Santos-Brault of the Quantified Citizen health research platform.

Microdosing involves regular self-administration in doses small enough to not impair normal cognitive functioning. The doses can be as small as 0.1 to 0.3 grams of dried mushrooms and taken three to five times a week.

The most widely reported substances used for microdosing are psilocybin mushrooms and LSD. Psilocybin mushrooms are considered non-addictive and relatively non-toxic—especially when compared to tobacco, opioids and alcohol.

“Our findings of mood and mental health improvements associated with psilocybin microdosing align with previous studies of psychedelic microdosing, and add to them through the use of a longitudinal study design and large sample that allowed us to examine consistency of effects across age, gender and their mental health,” says Rootman.

The comparisons of microdosers to non-microdosers over the one-month period of the study indicated greater improvements among microdosers when asked about their mood, depression, anxiety and stress, he explains. Analyses of the finger tap test showed that microdosers demonstrated a more positive change in performance than non-microdosers, particularly among people over the age of 55.

“Despite the promising nature of these findings, there is a need for further research to more firmly establish the nature of the relationship between microdosing, mood and mental health, and the extent to which these effects are directly attributable to psilocybin rather than participant expectancies about the substance,” says Dr. Walsh.

The study was not designed to investigate the potential influence of participant expectancy on microdose outcomes, but the authors note this is a necessary advancement in the field.

“Considering the tremendous health costs and ubiquity of depression and anxiety, as well as the sizable proportion of patients who do not respond to existing treatments, the potential for another approach to addressing these disorders warrants substantial consideration,” Rootman says.

The post Psychedelic mushroom microdoses can improve mood, mental health appeared first on UBC Okanagan News.