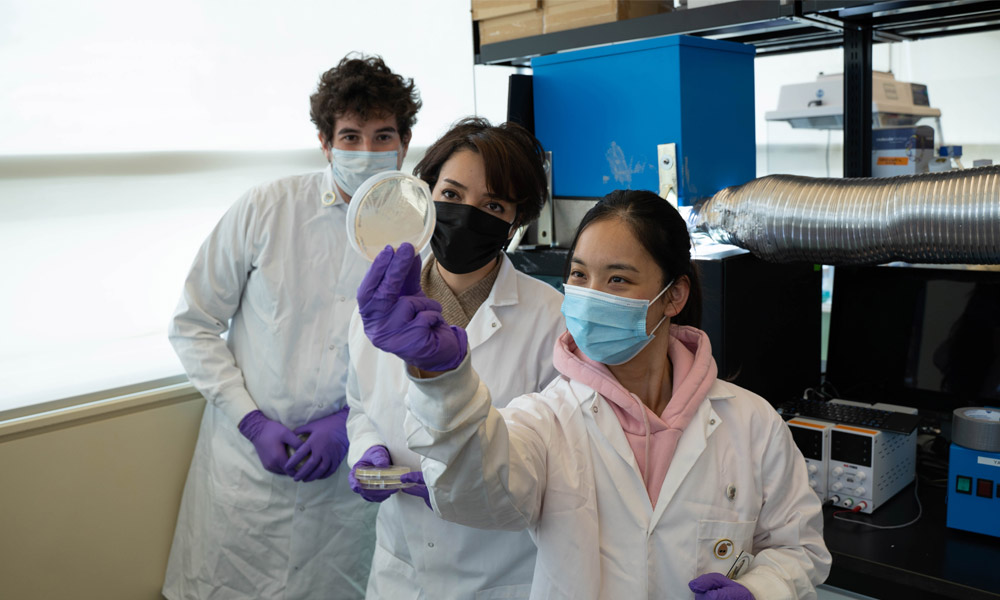

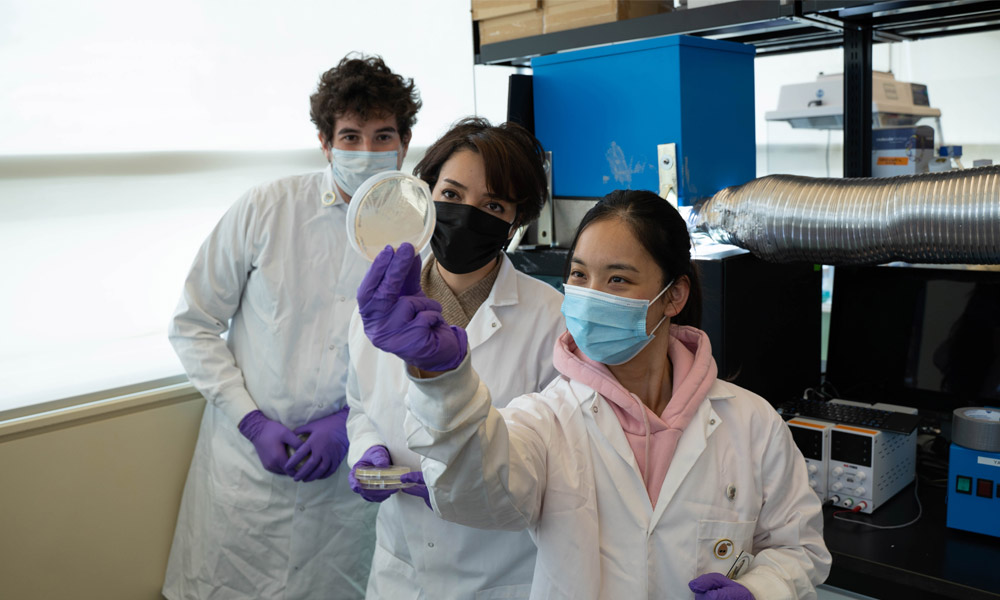

UBC Okanagan Assistant Professor Dr. Sepideh Pakpour, along with student researchers Enrique Calderon and Rita Lam, examine a sample beside the natural light experimentation chamber. Their research suggests light through smart windows can work as a natural disinfectant against many illnesses including E.Coli and methicillin-resistance Staphylococcus aureus.

Daylight passing through smart windows results in almost complete disinfection of surfaces within 24 hours while still blocking harmful ultraviolet (UV) light, according to new research from UBC’s Okanagan campus.

Dr. Sepideh Pakpour is an Assistant Professor at UBC Okanagan’s School of Engineering. For this research, she tested four strains of hazardous bacteria—methicillin-resistance Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, E. coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa—using a mini-living lab set-up. The lab had smart windows, which tint dynamically based on outdoor conditions, and traditional windows with blinds. The researchers found that, compared to windows with blinds, the smart windows significantly reduce bacterial growth rate and their viability.

In their darkest tint state, Dr. Pakpour says smart windows blocked more than 99.9 per cent of UV light, but still let in short-wavelength, high-energy daylight which acts as a disinfectant. This shorter wavelength light effectively eliminated contamination on glass, plastic and fabric surfaces.

In contrast, traditional window blinds blocked almost all daylight, preventing surfaces from being disinfected. Blinds also collect dust and germs that get resuspended into the air whenever adjusted, with Dr. Pakpour noting previous research has shown 92 per cent of hospital curtains can get contaminated within a week of being cleaned.

“We know that daylight kills bacteria and fungi,” she says. “But the question is, are there ways to harness that benefit in buildings, while still protecting us from glare and UV radiation? Our findings demonstrate the benefits of smart windows for disinfection, and have implications for infectious disease transmission in laboratories, health-care facilities and the buildings in which we live and work.”

The pandemic has elevated concerns about how buildings might influence the health of the people inside. While particular attention has been paid to ventilation, cleaning and filtration, the importance of daylight has been ignored. According to research shared in a recent Harvard Business Review, office workers are pushing for “healthy buildings” as part of the return to work and consistently rank access to daylight and views among their most desired amenities.

“Our buildings need to go beyond sustainable and smart to become healthy and safe environments first and foremost,” says Dr. Rao Mulpuri, Chairman and CEO at View, the company partnering with UBC for this research. “Companies are grappling with how to bring their people back to the office in a safe way. This research provides yet another reason why increased access to natural light needs to be part of the equation.”

The research was sponsored with joint funding from View Inc. and the Canadian government through MITACS, a not-for-profit organization that fosters growth and innovation in Canada by solving business challenges with research solutions from academic institutions.

The results of the research are particularly important for laboratories and health-care facilities. Sterile spaces are critical in labs, where sensitive materials must be protected from UV radiation and environmental contamination.

Extensive studies have shown that pathogenic bacteria and fungi can persist on inanimate surfaces for prolonged periods, leading to disease transmission. This is especially concerning in health-care settings, says Dr. Pakpour, where health-care-associated infections and outbreaks are often linked to contamination of curtains, windows, medical devices and other high touch surfaces despite current cleaning protocols.

“With the rise of antimicrobial resistance, antibiotics are no longer a silver bullet in treating health-care-associated infections, which cause tens of thousands of deaths in the US each year,” says Dr. Tex Kissoon, Vice Chair of the Global Sepsis Alliance, UBC Children’s Hospital Endowed Chair in Acute and Critical Care for Global Child Health. “The potential for daylight to sterilize surfaces and avoid these infections altogether is promising and should be factored into health-care facility design.”

Dr. Pakpour presented her findings earlier today at the international Healthy Buildings Conference, organized by the International Society of Indoor Air Quality and Climate. The research paper will be published shortly in Life Sciences and can be accessed at: biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.01.14.476401v1

“Passive environmental strategies, like allowing daylight through windows without blinds, can help keep the risk of infections down,” says Dr. Pakpour. “Our findings demonstrate the benefits of smart windows for disinfection, and have implications for infectious disease transmission in laboratories, health care facilities and the buildings in which we live and work.”

About Mitacs

Mitacs is a not-for-profit organization that fosters growth and innovation in Canada by solving business challenges with research solutions from academic institutions.

About View

View is the leader in smart building technologies that transform buildings to improve human health and experience, reduce energy consumption and carbon emissions, and generate additional revenue for building owners. View Smart Windows use artificial intelligence to automatically adjust in response to the sun, increasing access to natural light and unobstructed views while eliminating the need for blinds and minimizing heat and glare. Every View installation includes a cloud-connected smart building platform that can be extended to reimagine the occupant experience. View is installed and designed in over 90 million square feet of buildings including offices, hospitals, airports, educational facilities, hotels and multifamily residences. For more information, please visit view.com.