A prolific plant, bamboo has long been considered a good building material in many countries. Now, UBC Okanagan researchers have created a way to make it even stronger. Photo by kazuend on Unsplash

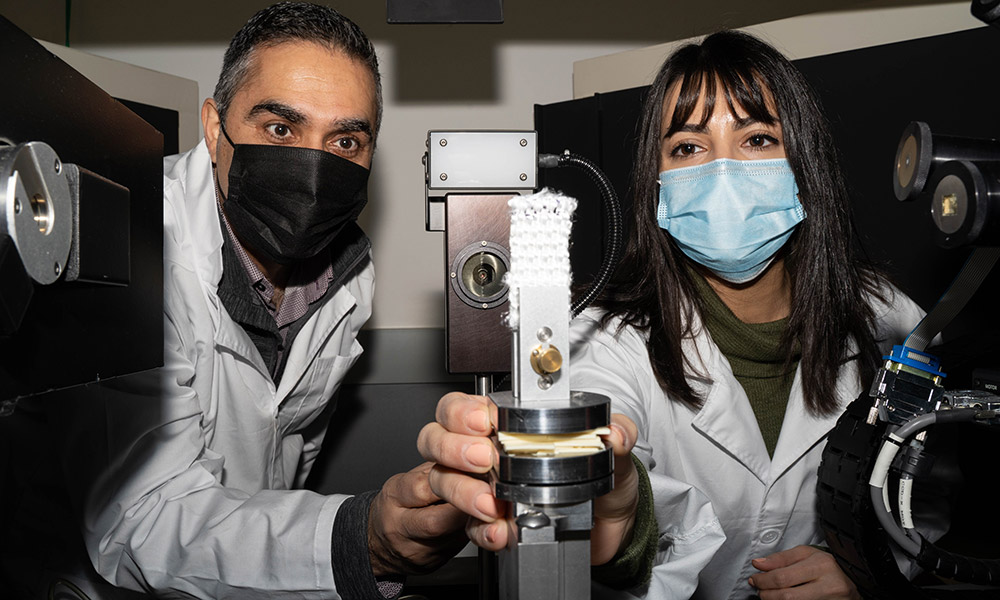

UBC Okanagan researchers have adapted a technique—originally designed to embalm human remains—to strengthen the properties of biocomposites and make them stronger.

With the innovation of new materials and green composites, it is easy to overlook materials like bamboo and other natural fibres, explains UBCO Professor of Mechanical Engineering Dr. Abbas Milani. These fibres are now used in many applications such as clothing, the automotive industry, packaging and construction.

His research team has now found a way not only to strengthen these fibres, but reduce their tendency to degrade over time, making them even more environmentally friendly.

“Bamboo has nearly the same strength as a mild steel while exhibiting more flexibility,” says Dr. Milani, the founding director of the Materials and Manufacturing Research Institute. “With its low weight, cost and abundant availability, bamboo is a material that has great promise but until now had one big drawback.”

Bamboo is one of the world’s most harvested and used natural fibres with more than 30-million tonnes produced annually. However, its natural fibres can absorb water and degrade and weaken over time due to moisture uptake and weathering.

Using a process called plastination to dehydrate the bamboo, the research team then use it as a reinforcement with other fibres and materials. Then they cure it into a new high-performance hybrid biocomposite.

First developed by Gunther von Hagens in 1977, plastination has been extensively used for the long-term preservation of animal, human and fungal remains, and now has found its way to advanced materials applications. Plastination ensures durability of the composite material for both short- and long-term use, says Daanvir Dhir, the report’s co-author and recent UBC Okanagan graduate.

“The plastinated-bamboo composite was mixed with glass and polymer fibres to create a material that is lighter and yet more durable than comparable composites,” says Dhir. “This work is unique as there are no earlier studies investigating the use of such plastinated natural fibres in synthetic fibre reinforced polymer composites.”

Dhir says this new durable hybrid bamboo/woven glass fibre/polypropylene composite, treated with the plastination technique has a promising future.

Supported by industrial partner NetZero Enterprises Inc., the research shows that adding only a small amount of plastinated materials to the bamboo can increase the impact absorption capacity of the composite—without losing its elastic properties. This also lowers the material’s degradation rate.

More work needs to be done on the optimization of this process as Dhir says plastination is currently time-consuming. But he notes the benefit of discovering the right composition of plastinated natural fibres will result in a sizable reduction of non-degradable waste in many industries, with a lower environmental footprint.

Future studies are underway to optimize and investigate the effect of plastinating other natural fibres, such as flax and hemp. The researchers also suggest a life cycle analysis of the materials should be conducted under different applications and compared to non-plastinated samples. This will provide a better picture of the corresponding trade-off between the environmental footprint and mechanical durability effects.

“Biocomposites continue to find new applications under the circular economy paradigm,” adds Dr. Milani. “The innovations in the methods used to develop these composites will ensure benefits well into the future.”

The research appears in the Journal Composite Structures.

The post UBCO researchers use unique ingredient to strengthen bamboo appeared first on UBC Okanagan News.