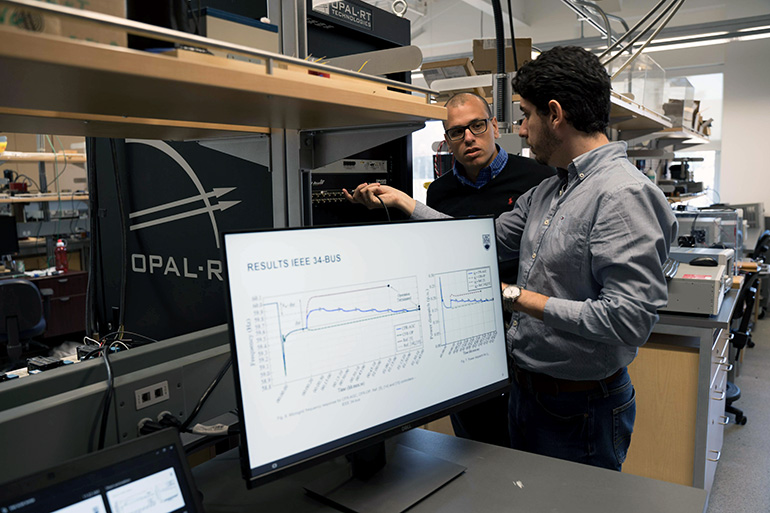

UBCO’s Morad Abdelaziz and Yuri Rodrigues have been researching the impact microgrids would have on the distribution and conservation of electrical power.

Researchers shine a light on ways to keep the energy flowing

With the goal of eliminating brownouts and blackouts, new research from UBC’s Okanagan School of Engineering is redesigning how electricity is distributed within power grids.

The research describes a power system operation that will consist of multiple microgrids—separate grids operating like individual islands that can disconnect from the main power supply and run independently.

These islanded systems will provide electricity to smaller geographical areas, such as cities and large neighbourhoods. In the case of a failure in the main system, the local grid operation system will keep the lights on.

“The microgrid will recognize the problem in the main power system and will isolate itself, avoiding previously inevitable power outages,” explains Yuri Rodrigues, a UBCO electrical engineering doctoral student and study co-author.

He explains, however, that a continued supply of power in this mode will depend on locally available generating reserves. This means that conserving energy is vital to keeping the islanded grid operational for as long as possible.

Rodrigues describes their approach as the difference between using the sports mode on your car versus the eco mode. The microgrid can distribute power at a slightly diluted level that won’t negatively impact electronics while allowing power to flow for longer periods without running out.

“Our new proposed method takes a more sustainable approach, allowing the microgrids to conserve power so any shortfall can be better handled by the microgrid itself,” Rodrigues says.

The challenge with using this concept in a larger system is that those larger systems may experience too much instability—this could result in the entire system shutting down. Rodrigues points to a similar occurrence in 2003 when most of the eastern seaboard of North America collapsed leaving millions in the dark.

Many safeguards already exist within power distribution systems to enlarge the system operation, but they only help by prioritizing power based on urgency, meaning hospitals and infrastructure would take precedence over regular consumer needs, he says.

This new approach of conserving power that is distributed within microgrids and thereby reducing or eliminating brownouts and blackouts could soon be an option for power systems around the world. It would also allow for global energy conservation that would decrease the network's demand and improve the self-sufficiency of the microgrid as a whole.

According to Rodrigues, their testing indicates this approach can significantly enhance microgrid autonomy and stability with no impact on the wider power system.

“There are many components that make up a power system from generation to distribution before electricity arrives in the outlets of consumers,” says Rodrigues. “Creating a system this is more self-sufficient, robust and sustainable is key to creating a reliable and blackout-free experience for future power consumers.”

The research, published in the Journal of Electrical Power and Energy Systems, was supported by several agencies in Brazil and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

About UBC's Okanagan campus

UBC’s Okanagan campus is an innovative hub for research and learning founded in 2005 in partnership with local Indigenous peoples, the Syilx Okanagan Nation, in whose territory the campus resides. As part of UBC—ranked among the world’s top 20 public universities—the Okanagan campus combines a globally recognized UBC education with a tight-knit and entrepreneurial community that welcomes students and faculty from around the world in British Columbia’s stunning Okanagan Valley.

To find out more, visit: ok.ubc.ca