UBCO’s Dr. Shahria Alam has receive two significant awards of recognition for his work this year, including being named a Fellow with the American Society of Civil Engineers, one of the highest recognitions of professional distinction within the field.

It has been quite a year for UBC Okanagan’s Dr. Shahria Alam.

The soft-spoken professor of civil engineering is internationally known as a pioneer in advancing sustainable construction practices.

And Dr. Will Hughes, Director of UBCO’s School of Engineering, says he’s also regarded as one of the world’s best at helping society prepare for the worst disasters imaginable, as evidenced by the numerous breakthroughs in climate change and disaster-resilient infrastructure he’s made in a career as a civil engineer that’s lasted more than 25 years.

Dr. Alam’s exemplary contributions to the field have earned him not one, but two impressive accomplishments this year—accolades that, like the impact of his research, teaching and mentorship, span borders and disciplines, explains Dr. Hughes.

In November, Dr. Alam was awarded the designation of Fellow by the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE), one of the highest professional distinctions within the field.

The honour marks Dr. Alam’s second career-defining milestone of the year.

In June, he was named a Fellow of the Canadian Society for Civil Engineering (CSCE)—a plaudit reserved for those who have demonstrated excellence and who have contributed actively towards the progress of the civil engineering profession.

Dr. Hughes says these back-to-back honours speak to Dr. Alam’s deep commitment to sharing his knowledge and to training highly qualified engineers who will also make a positive impact on countless organizations, institutions and municipalities around the world.

“Each of these Fellow designations is a lifetime achievement, and earning both in the same year is extraordinary,” he adds. “Through his continual pursuit of excellence, he consistently models to our students and his colleagues that our best work and most important discoveries are always ahead of us. On behalf of the School of Engineering, congratulations to Dr. Shahria Alam on this well-deserved recognition.”

For Dr. Alam, the Fellowships serve as milestones marking the progress of a lifelong journey and he notes a sense of gratitude to his mentors, colleagues, students and family members who have been instrumental in his professional career path.

“Becoming a fellow of both ASCE and CSCE in the same year is an extraordinary honour that feels both humbling and deeply affirming,” says Dr. Alam. “Being named a Fellow by ASCE, with its longstanding legacy and global reach, validates the significance of my work within a community I hold in the highest regard. Similarly, the CSCE Fellowship reinforces my connection to Canadian civil engineering, encouraging me to further contribute to the resilience and sustainability of infrastructure in Canada and beyond.”

“These honours are also profoundly motivating. They remind me of the responsibility I have to continue pushing boundaries, not just in research but also in supporting the next generation of engineers,” he says. “This dual recognition in a single year represents a unique moment, filling me with deep gratitude and renewed inspiration to keep contributing to our profession and society with renewed purpose.”

Dr. Alam and his research group’s work has garnered extensive interest across academia, industry, government and media, including recent work on the topics of building better infrastructure for climate resilience and the carbon costs of the construction industry. Among other projects, he is currently working with industry and government partners to research, test, and apply a sustainable, low-carbon waste material—wood ash—into concrete, as also highlighted recently by the Government of Canada.

“At UBC Okanagan, we take pride in fostering an environment that supports excellence in teaching, outstanding research, and positive impacts in communities, both local and global. Dr. Shahria Alam stands out as someone who is adept in each of these areas and who understands them appropriately as closely related,” says Dr. Lesley Cormack, UBC Okanagan’s Principal and Deputy-Vice Chancellor.

“Dr. Alam’s dedication to furthering sustainable construction and speeding the adoption of innovative, climate-resilient infrastructure has made—and continues to make—a tremendous impact on our campus and far beyond. These two fellowships are a testament to his celebrated contributions and creative solutions as a civil engineer and the extremely high regard with which he is held by his peers throughout North America.”

In addition to serving as a full professor for UBCO’s School of Engineering, Dr. Alam is the technical lead of UBCO’s Green Infrastructure Cluster and holds the Tier-1 Principal’s Research Chair in Resilient and Green Infrastructure. He is also the founding director of the Green Construction Research & Training Center (GCRTC), a joint initiative between UBCO and Okanagan College, dedicated to advancing sustainable construction and reducing the carbon footprint of the construction industry.

Recently, he was appointed as the acting Director of the Materials and Manufacturing Research Institute at UBC, where he continues to drive innovative research in sustainable materials.

“This work is vital to Canada and the world because it addresses critical challenges in building resilient, sustainable infrastructure—foundations essential for economic stability, environmental stewardship and societal wellbeing,” said Dr. Alam. “As climate change, urbanization and resource constraints increasingly impact communities globally, developing innovative approaches to resilient and green infrastructure has never been more urgent.

Collaboration has long been a cornerstone of Dr. Alam’s approach. He works extensively with researchers across disciplines, spanning many countries, including those from Canada, the United States, Japan, Italy, Qatar, United Arab Emirates, China, India and Bangladesh.

He’s also known for his dedication to his students and to training the next generation of civil engineers.

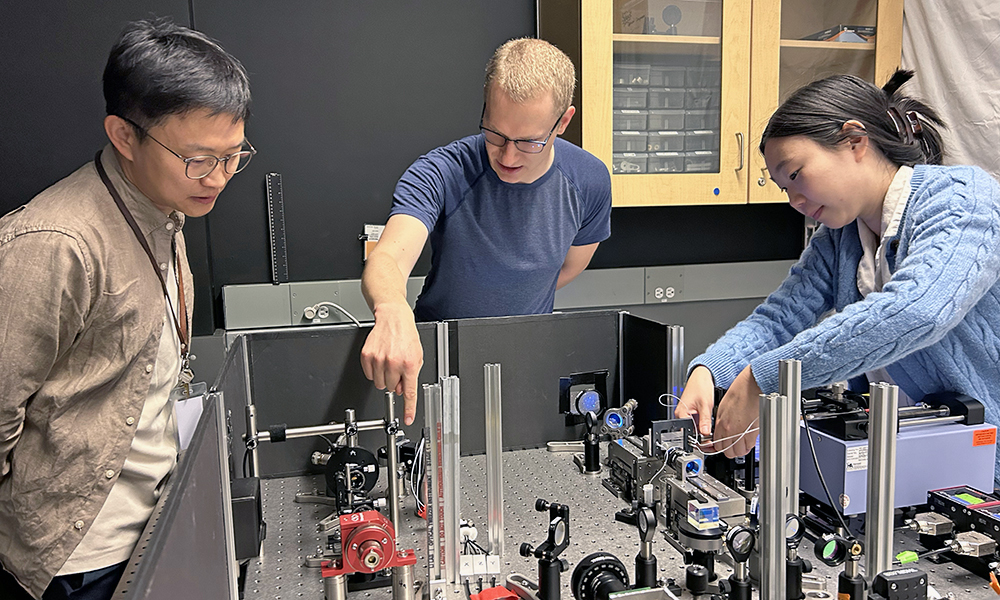

As the director of the Applied Lab for Advanced Materials and Structures at UBCO, Dr. Alam and team are currently training more than 30 postdoctoral fellows, graduate and undergraduate student researchers.

“Training highly qualified personnel is one of the most rewarding and essential aspects of my career,” says Dr. Alam. “Teaching, supervising and mentoring are far more than academic responsibilities—they are my contributions to the future of civil engineering, resilient infrastructure and the world.”

The post UBCO engineering professor earns recognition from top professional fellowships appeared first on UBC Okanagan News.