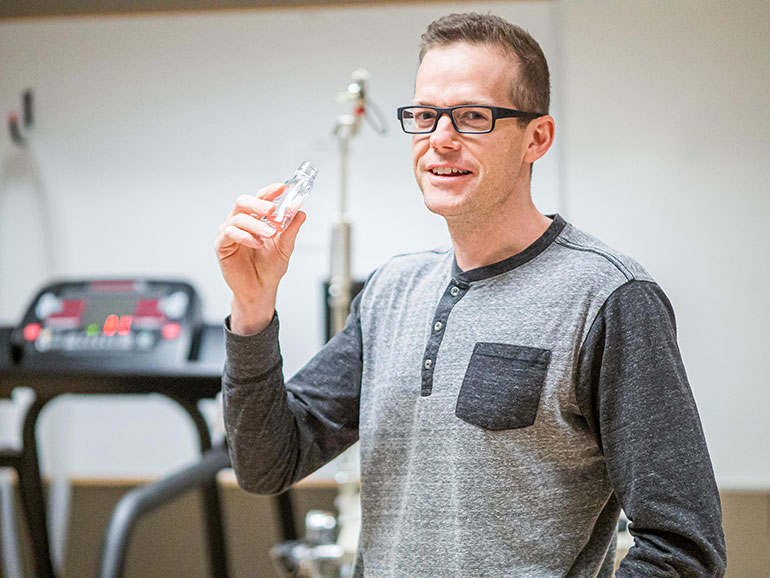

Rebecca Tyson, associate professor of mathematical biology.

Research links polarization, echo chambers to the spread of disease

Understanding how disease is passed from one individual to another has long been key to protecting populations from diseases like COVID-19. But new research from UBC’s Okanagan campus suggests that polarized opinions and apathy towards taking action can move through society like a virus and can seriously endanger efforts to contain a pandemic.

Rebecca Tyson is an associate professor of mathematical biology at UBC Okanagan and study lead author. She says that opinions and behaviours—like engaging in frequent hand washing, avoiding physical contact, or taking the threat of a pandemic seriously—can themselves spread throughout society and play an important role in how disease is transmitted during an epidemic.

“While we didn’t have COVID-19 specifically in mind when we conducted our research, we did try to imagine an epidemic that didn’t have a vaccine and that was best prevented by hand washing and other relatively simple actions,” says Tyson. “Behaviours like these can have extremes on either end of the spectrum, from denying the problem and doing nothing to completely isolating oneself.”

Using a mathematical model for both the spread of opinion—or opinion dynamics—and the spread of disease, she and her team were interested in how the presence, distribution and transmission of extreme behaviours can influence the epidemiology of a pandemic. They were particularly interested in how quickly a pandemic can take hold, the infection peak, the final number of those infected and the risk of a second peak.

“Our results show that opinion dynamics have a profound effect on the progression of disease in a population,” says Tyson. “In particular, the state of public opinion at the onset of a pandemic can have enormous influence—either dramatically reducing the fraction of the population that will be infected and the peak epidemic size, or making the epidemic worse than it would be otherwise.”

Tyson points to Hong Kong as an illustrative case of a population that was quick to adopt physical distance rules and were highly compliant with government regulations to eliminate spread, noting that COVID-19 is largely under control there. She adds that other countries, where compliance with government regulations was lower or slower, are having a much harder time.

While she’s quick to point out that her research is focused on mathematical models, she adds that the current COVID-19 outbreak is already showing some of the same outcomes she predicted in her models.

“Our models show that when faith in opinion influencers, like public health officials, is high, extreme preventative behaviours like quarantine and social distancing spread quickly through the population and the pandemic slows,” says Tyson. “This is exactly what we’re seeing in places like Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore and South Korea.”

On the other hand, Tyson says that populations that are politically polarized can see the disease spread much more quickly. Extreme behaviours, like disbelief in the problem, are amplified through influencer ‘echo chambers,’ which include mainstream or social media, creating pockets where the disease can spread more quickly.

“I believe this is part of the issue in the United States, where faith in government and public health officials is perhaps weaker than it is elsewhere and where there has been mixed messaging from different levels of government,” Tyson adds.

Looking to the future, she says her model shows that sustained and extreme physical distancing and hygiene behaviours are necessary to keep a highly-infectious disease at bay.

While the research provides a useful model for explaining the evolution of a pandemic, Tyson says that there are limitations.

“We assume things like a well-mixed population and we’re simplifying very complex human behaviour,” she says. “But there are definitely lessons in how opinion can shape the course of a pandemic and how we can leverage media and influencers to help keep public opinion from making a difficult problem worse.”

About UBC's Okanagan campus

UBC’s Okanagan campus is an innovative hub for research and learning founded in 2005 in partnership with local Indigenous peoples, the Syilx Okanagan Nation, in whose territory the campus resides. As part of UBC—ranked among the world’s top 20 public universities—the Okanagan campus combines a globally recognized UBC education with a tight-knit and entrepreneurial community that welcomes students and faculty from around the world in British Columbia’s stunning Okanagan Valley.

To find out more, visit: ok.ubc.ca